Impostor Syndrome- the organisations role in helping their people

By Helen Brooks for Pecan Partnership, March 2023

Do you ever experience feelings of being an ‘impostor’ at work? If so, have you ever wondered whether it’s an inevitable part of life? Or whether workplace culture can exacerbate it or reduce it?

It’s a common experience: 70% of people experience impostor syndrome at some point. Plus, there is increasing awareness of impostor syndrome, or impostor phenomenon as it is officially known. Much of the focus has been on what it is and how individuals can manage it. Organisations however can play a significant role in impostor syndrome, so in this article we look at the role organisations and leaders can play in helping with or exacerbating impostor thoughts.

What is Impostor Syndrome?

Impostor syndrome refers to individuals believing they are intellectual frauds, underestimating their competence and abilities despite objective evidence of high achievement.

Those experiencing impostor syndrome may:

- Set unachievable standards for themselves.

- Seek approval from others.

- Believe that they won’t be able replicate past achievements.

- Attribute their successes to having to work much harder than others, or as resulting from luck, error, or the contribution of others.

- Internalise and over-generalise mistakes or failure as evidence of professional incompetence.

My recent research into impostor phenomenon in management consultants looked at the triggers, coping strategies and the role of the organisation in helping individuals.

The findings on triggers of impostor thoughts align with that of wider research and include internal and external factors.

External triggers include:

- Interactions with others, such as senior meetings, being talked over or presenting to others.

- New projects or activities.

- Feedback or being positioned as an expert, with positive feedback being as triggering of impostor thoughts as negative feedback.

Internal triggers include:

- Internal perception of expertise, including making mistakes or not achieving self-imposed standards.

- Comparison of own experience to that of others, potentially overestimating the knowledge, experience and contribution of others and underestimating the self.

The impostor thoughts are not a valid, objective assessment of performance and are instead based on negative cognitive distortions. Impostor syndrome is not linked to actual performance, and many high achievers experience impostor thoughts extensively. Initially identified in women in the 1970s, it has been found to be prevalent across genders, ages, ethnicities, and professions. As noted above, research suggests that 70% of people experience impostor thoughts at some point in their professional lives.

If impostor syndrome is so prevalent, is it a ‘thing’ or just part of life?

With it being so prevalent, some have questioned whether impostor syndrome is a valid concept or just a natural part of life. The key point here is around depth and frequency of experience. While limited and infrequent experience of impostor feelings may have no adverse effect, those who experience it frequently and deeply are at risk of detrimental personal and professional implications such as:

- Greater risk of depression, stress, emotional exhaustion and burnout.

- Reduced mental health and wellbeing.

- Reduced confidence and self-esteem.

- Reduced career planning and progression due to feelings of inadequacy.

- Reduced job satisfaction and motivation to lead.

The risk arises when those who experience only occasional or slight impostor thoughts assume that the experience of others is the same as their own and fail to appreciate it can have wider and more damaging effects.

If it is such an internal thought process, what is the role of organisations and employers?

While there has been much focus on individual management of impostor syndrome, others have recently argued that it results from bias in the workplace and is caused by females and minorities being repeatedly overlooked and undermined. Advocates of this perspective propose that impostor syndrome as a concept should stop being discussed, with the focus instead being on changing the workplace not the individual. While there are undoubtedly issues with inequality in the workplace that need to be resolved, given that impostor syndrome has been found to be prevalent across genders, ethnicities and ages, any interventions should reflect the full population experiencing significant impostor thoughts.

Organisations can play a positive or negative role in impostor thoughts. Research has shown that organisations can exacerbate the effects of impostor syndrome if the environment lacks psychological safety or places excessive demands on individuals. Equally, organisations can have a positive effect on disrupting the aforementioned negative thought cycles of impostor syndrome, reducing negative effects on job satisfaction and helping mitigate the work-life balance conflicts that can occur through working too hard.

How can organisations and leaders help?

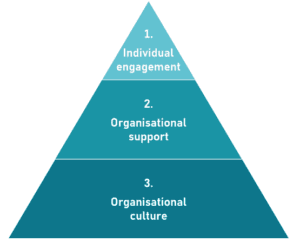

In my research, participant responses showed a real appetite for more impostor syndrome support from organisations. Looking at the combination of triggers and requests for support, a three tiered approach is proposed:

1. Individual engagement

In terms of individual engagement, organisations can focus on:

- Engagement prior to new activities and projects: It is natural to be apprehensive and to question abilities when starting something new, but people can be hesitant in sharing impostor thoughts due to fear of seeming incompetent. Cognitive distortions on capability therefore stay internalised, missing an opportunity for external support and challenge. Leaders can engage with people to understand what they are looking forward to, then ask about any concerns or apprehensions they hold, providing a gateway for more supportive mutual conversations.

- Providing positive feedback: The research showed positive feedback and being positioned as an expert to be triggering of impostor thoughts, but positive feedback is also key in providing people with objective data points to enable positive reframing of negative thoughts. It is important therefore for leaders to continue giving positive feedback but to ensure that it is authentic, based on specific actions and not always given in conjunction with areas for improvement. Leaders should also ask the recipient how they have processed the feedback and their thoughts on it. If the feedback has been ignored, discounted or produced a more negative response, this can be discussed further so that the recipient can ultimately take away useful insights to challenge future impostor feelings.

- Encouragement for career progression: A common feature of impostor syndrome can be holding back due to fear of failure. This holding back can particularly hinder career progression. As leaders, consider those in your team and the conversations about career progression you are having. If a team member is holding back, what assumptions are you making about that and how can you openly engage on what could be going on for them? The person may be quite happy where they are, but alternatively they could be experiencing self-limiting beliefs that not only hold them back but equate to a missed opportunity for the organisation to grow and develop key talent.

- Organisational support

Beyond one-to-one engagement with individuals, organisations can implement wider organisational support mechanisms such as coaching and mentoring to help build confidence and create insights to maximise individual potential. This can be accompanied by content specifically on impostor syndrome such as masterclasses and peer-to-peer conversations, making it a topic that is understood across the organisation so individuals can also effectively support each other.

- Organisational culture

Finally, consider the organisational culture. Leaders play a significant role in enabling an open and inclusive culture. When you, as a leader, share your vulnerability and a growth mindset in terms of learning from mistakes, others will feel safer doing so too. We noted earlier that environments that lack psychological safety exacerbate impostor thoughts. In professional environments it can feel that we are expected to be invincible so it can seem counter-intuitive to also be vulnerable or unsure – but it is human and the more, as leaders, we can be honest about that, the more we can create a culture where impostor thoughts are less prevalent and have a reduced impact.

Linked to that, it may seem obvious to value contributions from everyone but the feedback from my research suggests that people still don’t feel that is always the case. Really consider how inclusive a leader you are being to all styles and levels of contribution. What role could unconscious bias be playing in assumptions you could be making? How can you challenge this to encourage everyone in your organisation to feel psychologically safe and valued?

Concluding thoughts

By taking steps at each of the levels of individual engagement, wider organisational support and organisational culture, leaders and organisations can make changes that help individuals to better manage impostor thoughts. The actions also create wider benefits that help staff and their organisations as a whole to flourish and thrive.

About Helen

Helen is an experienced executive coach, working with senior individuals and global teams to help them maximise their potential and thrive.

As a management consultant for over 20 years, she worked with national and multinational clients across a wide range of industries on their most significant change initiatives. She combines her comprehensive understanding of the challenges, complexities and opportunities of professional working environments with strong knowledge of psychological theory and interventions from her psychology background. She holds an MSc in Positive Psychology and Coaching Psychology, which included conducting research into impostor syndrome.

If you have any questions about impostor syndrome or Helen’s work then please feel free to contact her at [email protected] or through her website.